She shares with her readers her discomfort in presuming to speak for those who have every reason to mistrust her use of their words, dialect, and experience.

In giving public voice to Henrietta’s children, as well as posthumously to their mother, Skloot demonstrates tensions and tenets of feminist narrative approaches and contemporary standpoint theories. Someone with more money and books behind her would have begun with a publicist, not a grassroots book tour worthy of studies in social networking and the importance of relationships (Skloot 2010). They, in turn, would have perceived and received the writer differently.

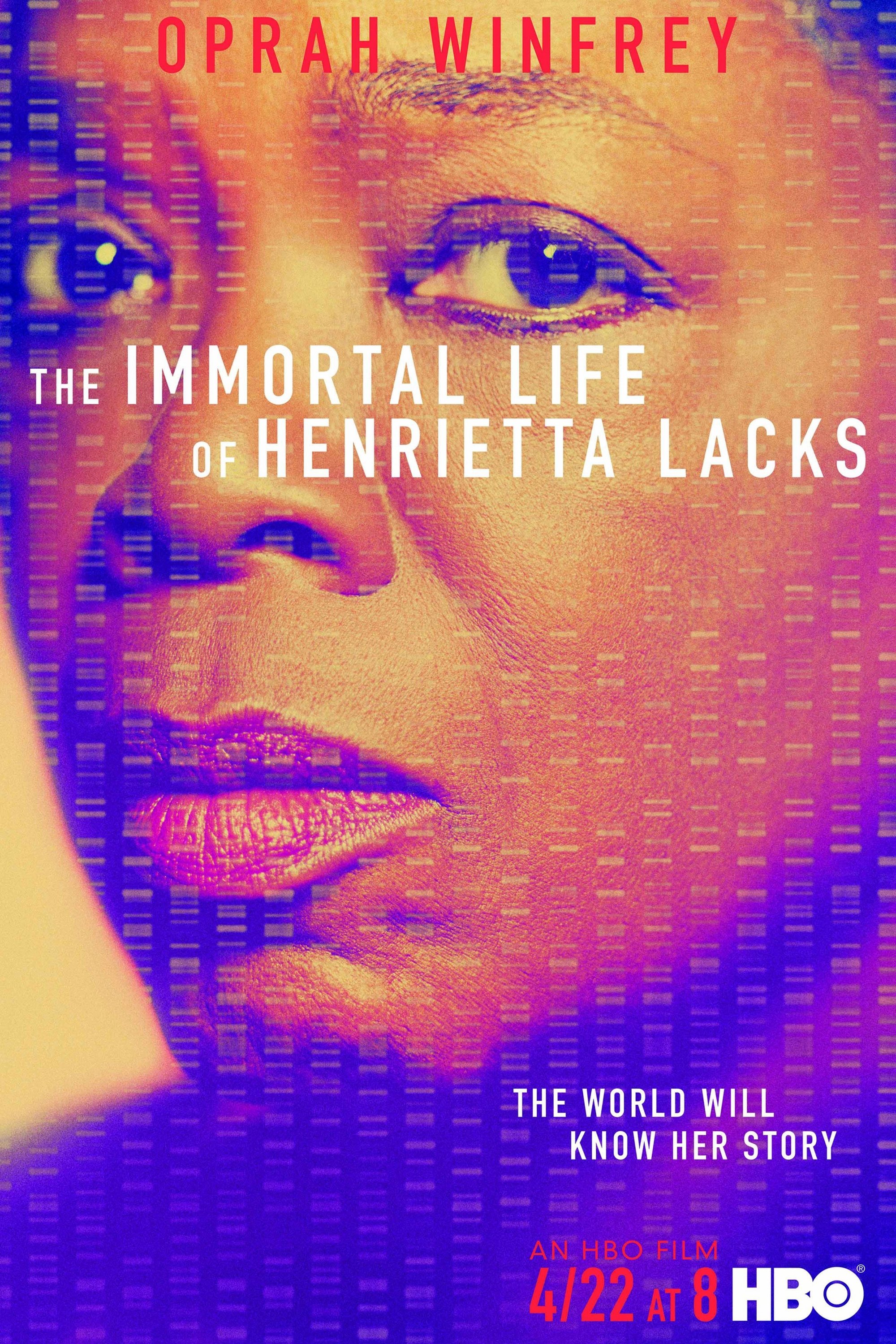

Someone differently situated from this young white woman from the North, who had an interest in genetics, a graduate degree in writing, and both sensitivity and gumption, would have approached Henrietta’s living relatives very differently. Someone who had not been haunted by the “black woman” behind the HeLa cell line since hearing the name “Henrietta Lacks” in community college biology class would have written a very different book. It is not just that an authorial voice is present throughout, but that Skloot shares and reflects on her interests, fears, and ethical quandaries. This is especially true since research ethics is an arena in which feminist insights have played a less explicit role than in other bioethical domains.Īccounting for some of the book’s popularity is the degree to which Skloot’s telling is explicitly personal. Yet it is worth examining how Skloot’s telling of Henrietta’s story illustrates, and provides an excellent opportunity to teach, feminist approaches in bioethics. So much has been written about Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks that it is difficult to offer fresh insight on this “science book” that has had a remarkable run on the New York Times best-seller lists. Henrietta died about eight months after seeking treatment. They became HeLa, the first immortal human cell line. Henrietta’s tumor cells thrived in culture, doubling every twenty-four hours. Before sewing a tube of radium into her cervix, the surgeon on duty took samples of tumor and healthy tissue, and as with many other samples taken from charity patients at Hopkins, handed the samples to researchers trying to develop an immortal human cell line (an important research tool, an immortal cell line is a population of cells from a multicellular organism that, due to mutations, do not lose their ability to divide at the point most cells do). Called back to Hopkins for treatment of diagnosed carcinoma of the cervix, Henrietta signed a one-line “Operation Permit,” and under general anesthesia received her first round of radium treatment. In 1951 Henrietta Lacks felt a lump in her cervix, entered Johns Hopkins Hospital, and was examined in a colored-only exam room by a physician who biopsied the lump.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)